BORING ON THE MILL

Introduction

Boring on

the mill is a simple operation in theory, but requires close attention to

detail for success when precision is important (i.e. to within 0.001” of target

size).

*** CAUTION ***

Please

understand that using a boring head on a milling machine is an inherently

dangerous process because the tool is deceptively dangerous when rotating, so YOU MUST KEEP YOUR HANDS AWAY FROM THE

CUTTING ZONE AT ALL TIMES WHEN THE MILL IS RUNNING.

Step 0: Understand EVERYTHING

Matters

Using a

boring bar to simply enlarge an existing hole is a straightforward

process. However, when trying to hit a

particular size and tight tolerance, everything begins to matter: boring bar

selection and setup, cutting edge geometry, tool deflection, lubrication,

cutting parameters, chip evacuation, part temperature, and our ability to

measure the bore accurately and precisely.

If you cannot force yourself to be a little OCD, you might not be good

at precision boring J.

Step 1: Boring Bar Selection

There are

three general types of boring bars: high speed steel, brazed carbide, and indexable carbide.

The benefits of HSS are that it is cheaper and tougher. The benefits of carbide are that it can

tolerate much more heat (i.e. it can cut 2.5 – 5 times faster than HSS), and it

has a modulus of rigidity that is about 2.5 times greater than steel.

Figure 1:

Examples of HSS boring bars.

Figure 2:

Example of brazed carbide boring bars, where a small piece of tungsten carbide

is brazed onto a cheaper steel shank.

When the carbide chips, the boring bar is either reground (which is

difficult to do well) or discarded.

Figure 3:

Example of indexable carbide boring bars, where a

replaceable tungsten carbide insert is attached to a machined pocket in a steel

or carbide boring bar shank. When the

carbide insert chips, it can be easily and quickly

rotated to another corner (indexed) or replaced with another insert.

Figure 4: Larger

corner radii are stronger and better for roughing, but smaller corner radii

typically produce more accurate bore sizes and better surface finishes (at

reduced feeds).

As with all

metal cutting processes, stiffness is key when boring,

so do everything you can to maximize it: use the largest diameter boring bar

and the shortest clamping length possible.

Step 2: Boring Bar Setup

It’s worth

repeating: as with all metal cutting processes, stiffness is key when boring,

so do everything you can to maximize it: use the largest diameter boring bar

and the shortest clamping length possible.

Figure 5:

Example of properly selected brazed carbide boring bars. Notice how short and stiff the selected bars

are in relation to the respective workpieces.

Many boring

bars do not have alignment flats on them, so it is necessary to orient the top

(flat) surface of the cutting edge so it passes through the centerline of the

spindle axis, as shown in figure 6. This

orientation is referred to as a neutral rake angle and is the safest for most

materials and the only orientation that works properly when using these types

of boring bars in a boring head. When

setting a boring bar with no alignment flats, it is always necessary to perform

a test cut to ensure the rake angle is set properly.

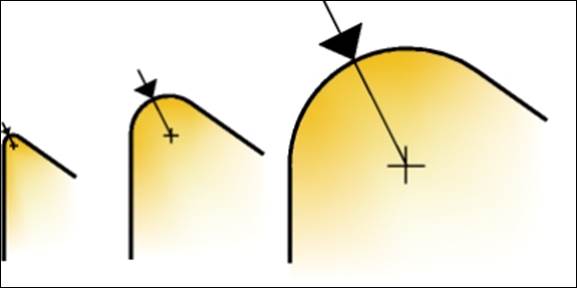

Figure 6:

Examples of possible boring bar orientations (negative (left), neutral

(center), and positive rake (right)).

ALWAYS use neutral orientation (center) in a boring head on a mill.

When setting

up the workpiece, always ensure adequate clearance exists beneath it and the

vise if boring a thru hole. Whether

boring a thru or blind hole, always set the quill depth stop appropriately to

prevent an over-travel condition, which would damage the part, the boring head,

and potentially the vise.

Figure 7: Set the quill depth stop before using the boring head.

Step 3: Selection of Cutting

Parameters

When using a

boring head on a milling machine, it’s best to begin with a cutting speed equal

to half the typical computed value and work your way up if vibration and tool

life allow it. The primary reasons are

the reduced stiffness due to the cantilevered nature of boring bars, as well as

the difficulty of providing consistent lubrication to, and chip evaluation

from, the cutting edge of the tool unless flood cooling, as in a CNC mill. For safety reasons due to the rotational

imbalance inherent in a boring head, never rotate the boring head faster than

600 rpm in the design lab.

Boring heads

on Bridgeport-size milling machines should usually not be used with depth cuts

deeper than 0.020”. It’s important to

understand there is also a safe minimum

depth of cut, below which the tool constantly transitions between cutting and

smearing, leaving a very inconsistent size and finish. This safe minimum depth of cut is typically

around 0.003” to 0.005” depending on the material. Harder / stronger materials can usually

tolerate a smaller minimum depth of cut, as can boring

bars with sharp corners.

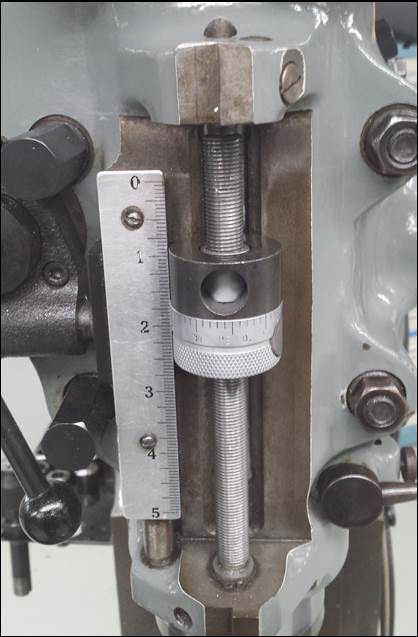

When making

depth adjustments, you can use the calibrated dial on the boring head, or a

dial indicator if trying to be as precise as possible, or using a worn boring

head.

Figure 8:

Example of using a dial indicator to adjust the boring head depth of cut. This isn’t always necessary, but it

facilitates more accurate adjustments.

Step 4: Bridgeport Automatic

Quill Feed

Bridgeport

milling machines have three choices for quill automatic quill feedrate: 0.001,

0.003, and 0.006 in/rev. The middle

speed typically works well for most work.

The

following schematic and accompanying video explain the function of the

automatic feed.

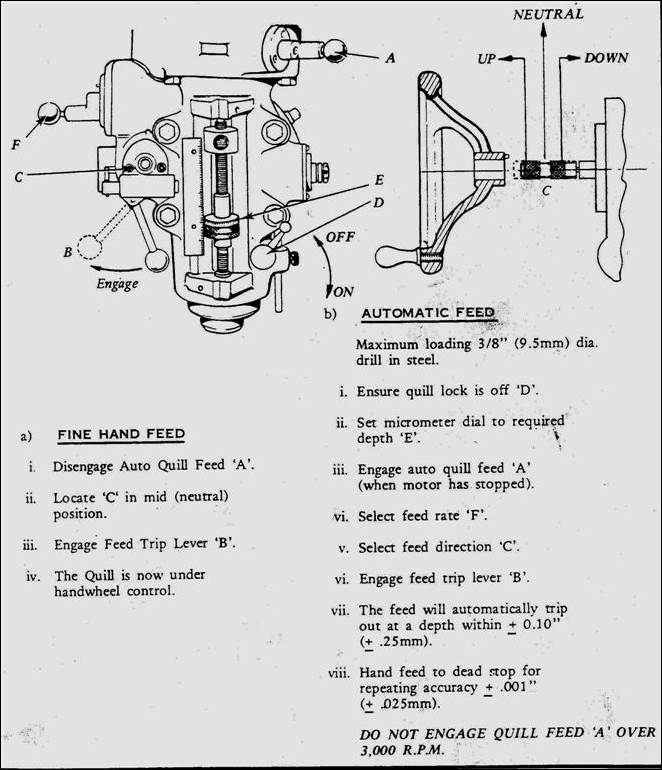

Figure 9:

Bridgeport automatic quill feed explained.

Click for

short video illustrating its use.

Step 5: Ideology for Repeatable

Results

Consistency

is crucial to obtaining repeatable results when using boring heads. Meaning, you want to vary the fewest

parameters possible during each cut, and preferably only one at a time. Anything that affects the cutting force at

the tool tip will change the amount of material removed, or the surface finish

obtained: depth of cut, feedrate, lubrication, corner radius, part temperature,

etcetera.

Let’s say you are trying to thru-bore a 1” hole in a

piece of 303 stainless steel. One approach would be as follows:

1.

Remove as

much material as possible by drilling, since it’s the most efficient method of

material removal. When doing this, be

sure to leave enough stock for the next step.

Leave the bore about 0.050” small in this case.

2.

Perform a

few test cuts to check how the boring bar is cutting. Rarely will a boring bar cut perfectly. If you try to remove 0.010” off the diameter

of the bore, it may only remove 0.0096” on the first pass and another 0.0004”

on the spring pass. (A spring pass is

simply a second pass that helps compensate for tool or part deflection during

the first pass.) It’s important to make a couple passes and write down how much each

removes so you can take the average and know what to expect when it matters.

3.

Do not try

to “sneak up” on the final size. As

anti-intuitive as it may sound, the best results are not obtained by making

smaller and smaller cuts until you reach the desired size because of the safe

minimum depth of cut discussed in Step 3 above.

The best results are obtained by repeatedly removing a similar amount of

material on each pass and using the resulting measurement data to make small

adjustments to each subsequent pass. On

the 1” 303 example piece, the final cut would remove 0.005” to 0.010” from the

diameter to bring the part into final size tolerance.

Step 6: Bore Measurement

Bore

measurements can be made using several tools, depending on the budget, operator

skill, and required measurement accuracy.

Dial or Digital Calipers

The easiest

tool to use for bore measurement is also the least accurate: dial

calipers. These typically aren’t very

accurate (within a couple thousandths of an inch) on smaller bores because the

inside jaws have flats ground into them that prevent them from measuring the

true size of the hole.

Figure 10:

Measuring larger bores with dial or digital calipers.

Inside Micrometers

The second

easiest tool to use is an inside micrometer.

However, inside mics typically only work well for measuring shallow

bores up to approximately 3” in diameter.

They are accurate to +/-0.001”.

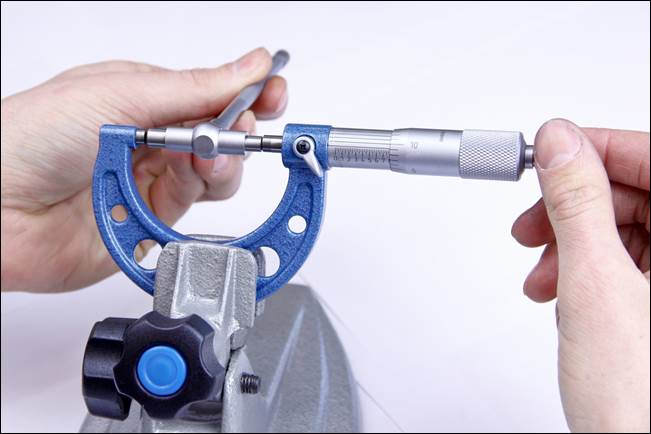

Figure 11:

Inside micrometers used to measure a precision bore.

Small Hole Gages

Next are

small hole gages, which are also inserted into a bore

until a small amount of drag is felt and subsequently measured with outside

mics. Used in sensitive hands, small

gages are accurate to +/-0.002”.

Figure 12:

Example of small hole gages.

Gage Pins

Gage pins

are another way to measure precision holes.

Gage pins are available in virtually any size and typically manufactured

(precision ground) to +/-0.0002” tolerance.

Figure 13:

Gage pin assortment used to measure precision bores.

Telescoping Gages

Telescoping

gages are commonly used to measure bores, but require a lot of operator skill

to provide repeatable and accurate results.

After being inserted into the bore, a small amount of torque is applied

to a friction lock, the telescoping gage is swept

through the center of the bore, and subsequently measured with a

micrometer. The challenge is applying

the proper amount of torque to the friction lock, as too little results in the

gage not holding the true bore reading once removed, and too much

results in the gage distorting and showing a reading that is larger than

the actual bore size. Like all metrology

tools, practicing on a bore of known size (like a bearing race for example) is

the only way to become proficient in the use of telescoping gages. Used in sensitive hands, telescoping bore

gages are accurate to around +/- 0.0015.

Figure: 14:

Using telescoping gages and outside mics to measure bore diameters.

Bore Gages

Bore gages

are essentially precision telescoping gages with dial indicators built in. In use they are first calibrated using an

outside micrometer and then the actual bore size is measured relative to that

calibration using the dial indicator . Bore gages are accurate to +/-0.0005”.

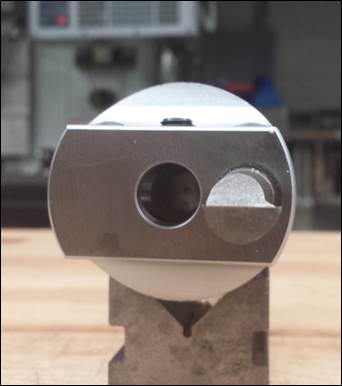

Figure 15:

Bore gage used to measure the bearing diameter of a connecting rod for an

automobile engine.

3 Point Micrometers

The best

tool for accurately measuring bores is a 3 point internal micrometer; however,

these are also the most expensive option because each has a limited measurement

range, so several units have to be purchased to cover a decent range of

sizes. 3 point micrometers are accurate

to +/-0.00005” to +/-0.0001”.

Figure 16: 3

Point Bore Micrometers.

Miscellaneous Tips